Encountering Poulenc

Francis Poulenc (1899 - 1963) was a French composer and pianist, and one of the members of Les Six.

I first came to know Poulenc through his Improvisation No. 7. It was one of the required pieces for a piano exam, and only then did I realize that this figure existed in the world of classical music. Upon first hearing it, I was deeply drawn to its rich harmonies. The piece begins in a simple and seemingly harmless C major. Then, as mysterious and ever-changing chords appear one after another, it becomes clear that it is far from simple. My favorite part is the heartbreaking opening of section B, followed by the majestic layers of octaves, and the return to C major after the climax has faded. Honestly, there are too many parts I love to list them all.

What kind of person writes such music? What were his thoughts about music? Any composers he likes or dislikes? My curiosity pushed me to search for more information, and here is some of what I found.

About Poulenc

Poulenc was born to a wealthy middle-class family in Paris in 1899. His father, Emile Poulenc, ran a pharmaceutical company, and his mother, Jenny (née Royer), came from a family of artistic craftsmen. Poulenc began learning piano at the age of five under his mother’s guidance, and shortly afterward she found other teachers for him. The teacher who influenced him the most was Ricardo Viñes, with whom he studied from age fifteen to eighteen. Viñes not only influenced Poulenc as a pianist but also became a spiritual mentor in his life. The second influential teacher was Charles Koechlin, whom Poulenc sought at the age of twenty-two, believing that his compositions relied too much on intuition rather than knowledge and hoping to strengthen what he lacked. Poulenc originally intended to attend a music conservatory, but his father insisted that he should first receive a conventional classical education at Lycée Condorcet before continuing music studies, so he followed. Unfortunately, both of his parents died before he turned eighteen, and later the outbreak of the World War I disrupted his plans. Yet none of that prevented his musical path. At eighteen, his Rhapsodie Nègre (FP 3) premiered in Paris, earning him the admiration of Igor Stravinsky, and the work was soon published by Chester in London.1

Reading Poulenc’s biography, I found myself resonating with some parts. When I was in junior and senior high school, I wanted to pursue music professionally, but my family objected. Later in college, I studied literature and originally planned to pursue a graduate degree in music afterward, but life unfolded differently. Around the age of twenty, believing that I lacked professional training, I also sought a teacher, only to later realize the teacher was not the right fit, which is another story. Looking back now, there is still a slight sense of regret, though less than before. Had I received formal conservatory training, I might have spent years studying subjects I was not passionate about, such as opera. I also might have missed the blessings that came from studying literature. Perhaps Poulenc’s freedom as a composer also had something to do with not going through a traditional conservatory system.

🗣️ Fun Fact 1: Was he an extrovert or an introvert?

Poulenc was very likely a strong extrovert, and the kind who could easily become the center of attention with entertaining stories. Many friends recalled that he was an excellent storyteller. If a gathering needed someone to lift the atmosphere, Poulenc could keep the stories flowing without end.🗣️🗣️🗣️ 2

📻 Fun Fact 2: A person who kept up with the times.

Poulenc kept surprisingly up to date with new technologies. When the gramophone was invented, he immediately used it to record his music. His earliest recordings date back to 1928. In his forties and fifties, seeing the growing influence of radio, he even hosted programs on French National Radio.3 If he lived today, I imagine he might start a podcast to talk about music. 🎙️

Poulenc’s Piano Works

How Not to Play Poulenc?

To understand how a piece should be played, aside from reading the score carefully, it is often helpful to hear what the composer does not want. In a conversation with Claude Rostand, Poulenc mentioned four things pianists should never do when performing his works: no rubato, do not hesitate to use the pedal, do not lengthen or shorten note values, and do not overarticulate repeated chords or arpeggios.

Poulenc greatly disliked rubato. Once a tempo was set, he preferred that it remain consistent unless a tempo change was specifically indicated. He could tolerate wrong notes more easily than altered durations. What mattered most to him was pedaling. Influenced by Viñes, Poulenc believed that the pedal could never be used too much. Even when Viñes used extensive pedaling, his sound remained clear, which impressed Poulenc deeply. When hearing performances with insufficient pedaling, Poulenc said he felt like shouting, “Put some butter in the sauce! What’s this diet you’re on!”4 (It does sound delicious. Would listening to Poulenc make one gain weight?😆)

I was surprised at first by this idea. Thinking more about it, I realized that my surprise came not from Poulenc’s music, but from my own assumption that less pedal is better. Perhaps it comes from fear that too much pedal will make the sound muddy. After reading his perspective on pedaling, I agreed that if the pedal is used well, it can enrich color while keeping clarity. It’s a good idea to give it a try.

How he evaluate his own piano music

Poulenc had strong opinions on how his works should be interpreted and was equally candid about judging his own music. I personally enjoy how straightforward he was. He said he could “tolerate” Mouvements perpétuels (FP 14), the Suite in C (FP 19), and Trois Pièces (FP 5). He deeply loved his Improvisations and the Intermezzo in A flat (FP 118). He completely disliked Napoli (FP 40) and Soirées de Nazelles (FP 84), and as for the rest, he felt little interest.5

He never explained in detail why. Out of curiosity, I listened to all the pieces he mentioned. Strangely, Mouvements perpétuels, which he only tolerated, is one I could loop repeatedly. Why did he like it less? Perhaps a creator’s taste does not always match that of the audience. Maybe this distance is something every artist must maintain. One cannot rely solely on public taste.

Composers Poulenc Liked and Disliked

In another interview, Rostand asked Poulenc to name six composers he loved. After much hesitation, he listed Debussy, Stravinsky, Satie, Falla, Ravel, and Bartók, and regretted not having room for Prokofiev.6 To Poulenc, Debussy awakened his musical sensibilities. Stravinsky, however, shaped his compositional language, and traces of Stravinsky are evident throughout Poulenc’s music.7 Ravel influenced his harmony, especially in Les Animaux modèles (FP 111). As for Satie, he shaped his sense of musical beauty.8

As for composers he disliked, Poulenc answered with humor and creativity. He did not like Brahms’ pieces, saying that Brahms had “Schumann’s faults without his genius."9 He also said he was allergic to Fauré’s music throughout his entire life.10 Nonetheless, he acknowledged their strengths. Brahms, in his view, was still a genius, and he admired Fauré’s songs. What’s worth noting is that his criticisms were not reckless hostility. Poulenc had studied these composers thoroughly from a young age.11

His interviews are delightful to read. Poulenc was witty, vivid, and full of imaginative comparisons. I appreciate how honest he was about his taste. Perhaps honesty is essential for artists to resist blindly following others. Even if Brahms and Fauré are widely beloved, what matters is whether Poulenc himself felt connected to them. Only by recognizing one’s own likes and dislikes can one find and walk their own paths.

Conclusion

There is far more to explore about Poulenc than what is written here. He cooperated with Pierre Bernac and wrote over ninety mélodies. He also composed many other types of works. (These classical masters were truly prolific.) Since instrumental music is my personal favorite, and within it, piano music most of all, this article focuses on his piano works. Maybe someday I’ll continue writing about his other compositions.

To close, I would like to share a recent performance of mine, playing the piece through which I first encountered Poulenc, Improvisation No. 7. I hope this is, in some small way, in keeping with Poulenc’s taste.

Bibliography

Chimènes, Myriam and Roger Nichols. “Poulenc, Francis.” Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.22202

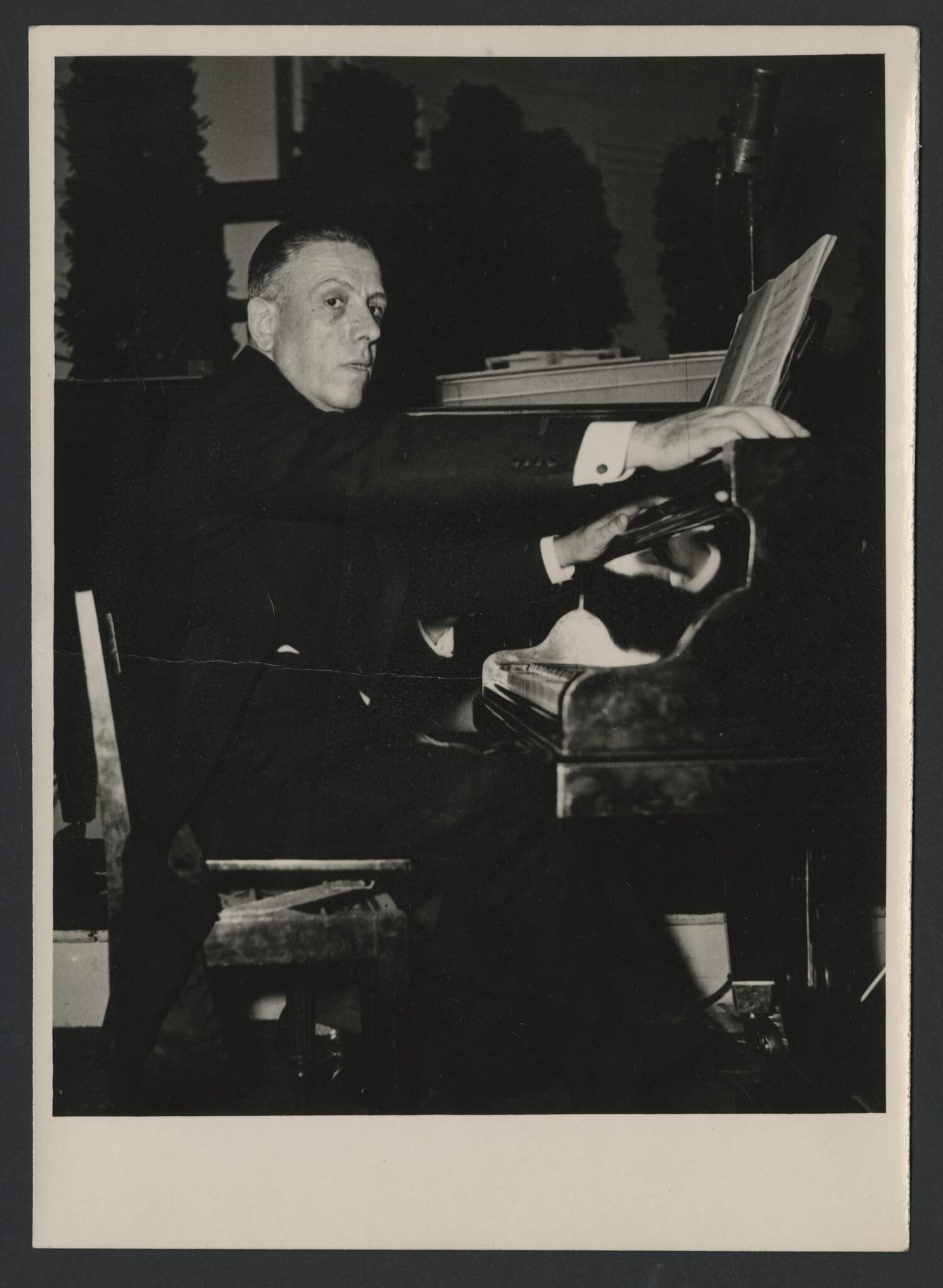

Editions de l’Oiseau-Lyre. “Francis Poulenc in a Suit, Sitting at a Piano with His Arms Outstretched.” 1946. University of Melbourne Archives. UMA-ITE-2016003500406. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://archives.library.unimelb.edu.au/nodes/view/431648

Poulenc, Francis. “Musical Likes and Dislikes.” Interview by Claude Rostand. In Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, edited by Nicolas Southon, translated by Roger Nichols, 273–278. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

Poulenc, Francis. “My Teachers and My Friends.” In Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, edited by Nicolas Southon and translated by Roger Nichols, 97–103. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

Poulenc, Francis. “Poulenc at the Piano: Advice and Favourites.” In Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, edited by Nicolas Southon, translated by Roger Nichols, 191–195. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

Southon, Nicolas. “Introduction.” In Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, edited by Nicolas Southon, translated by Roger Nichols, 1–14. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

NB: This article was first published in Chinese on 11/24/25. It was later translated with assistance from ChatGPT, edited by me, and published in English on 12/3/25.

Myriam Chimènes and Roger Nichols, “Poulenc, Francis,” Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press, 2001), 1–2. ↩︎

Nicolas Southon, “Introduction,” in Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, ed. Nicolas Southon, trans. Roger Nichols (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014), 9. ↩︎

Chimènes and Nichols, “Poulenc, Francis,” 2–3. ↩︎

Francis Poulenc, “Poulenc at the Piano: Advice and Favourites,” in Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, ed. Nicolas Southon, trans. Roger Nichols (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014), 193. ↩︎

Poulenc, “Poulenc at the Piano: Advice and Favourites,” 194. ↩︎

Francis Poulenc, “Musical Likes and Dislikes,” interview by Claude Rostand, in Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, ed. Nicolas Southon, trans. Roger Nichols (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014), 274. ↩︎

Poulenc, “Musical Likes and Dislikes,” 273. ↩︎

Poulenc, “Musical Likes and Dislikes,” 273-274. ↩︎

Poulenc, “Musical Likes and Dislikes,” 275. ↩︎

Poulenc, “Musical Likes and Dislikes,” 276. ↩︎

Francis Poulenc, “My Teachers and My Friends,” in Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart, ed. Nicolas Southon, trans. Roger Nichols (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014), 96. ↩︎

The photo was taken in 1946 when Poulenc is around 47 years old. This photo is in public domain and is from the University of Melbourne Archives. Link: https://archives.library.unimelb.edu.au/nodes/view/431648

The photo was taken in 1946 when Poulenc is around 47 years old. This photo is in public domain and is from the University of Melbourne Archives. Link: https://archives.library.unimelb.edu.au/nodes/view/431648